From Carbon Brief

From Carbon Brief

Flying back too early or too late for spring is costly for migratory birds. Their arrival must coincide with the emergence of food sources, such as caterpillars, in order to enable them to feed and successfully rear their young.

Birds that overwinter in warmer climes, including willow warbler, tree pipit and barn swallow, will be unable to cut their migrations short as climate change causes spring to arrive earlier in many parts of Europe, as new evidence suggests that some birds are much less adaptable to climate change than previously hoped.

Time to fly

Each winter, around half of the UK’s birds take off to find food in a more temperate climate, returning to their ancestral breeding grounds the following spring. However, scientists fear that this annual migration could be disrupted by climate change, which is causing spring to arrive six-to-eight days earlier in Europe than it did 30 years ago.

Evidence suggests that some birds will be able to adapt by leaving for their winter grounds later in the year or wintering closer to home (see BOTE report here). However, not all birds are able to perceive subtle shifts in temperature and instead rely on the number of daylight hours – which is unaffected by warming – to tell them when it’s time to fly.

For these birds, keeping pace with an earlier spring means getting back from their wintering grounds more quickly. But the solution isn’t as simple as flying at a faster speed because birds simply do not have the energy to beat their wings any harder during their lengthy migrations. A new study, published in Nature Climate Change, looks at a third option: reducing the length of “stopovers”. These are the avian version of a pit stop, where birds feed and rest before continuing their journey. While shorter stopovers can significantly speed up a migration, it’s unlikely to be enough, the study finds.

For example, cutting time spent resting by 50% would lead to birds arriving in their spring grounds just two days earlier, on average. In comparison, the peak availability of caterpillars – a key source of food for birds – in UK forests advanced by 20 days between 1980 and 2008. This mismatch between the arrival time of birds and their foods could spell trouble for many bird species that are unable to adjust the start of their spring migration, says lead author Dr Heiko Schmaljohann from the Institute of Avian Research in Germany:

“The inability to sufficiently adjust or adapt the breeding area arrival timing leads to an increasing mismatch between food availability and its demand. If this mismatch increases for a species population, it is possible that this may lead to a population decline.”

Schmaljohann adds that although there are some birds which seem to be adjusting their spring arrival date in response to climate change, such as the pied flycatcher, it is still not known which species are most at risk of decline:

“The pied flycatcher has advanced its breeding area arrival timing the most. Whether they have a better ability of detecting how conditions will be at the breeding area in one to two months is totally unknown. It is extremely unlikely that birds, being still at their African wintering grounds, can anticipate the environmental conditions they will experience at the breeding areas in advance.”

Calculating migration speed

To understand what drives the speed of a migration, the researchers reviewed data from 49 tracking studies of 46 different bird species.

They found that the overall migration speed is largely dependent on the number of stopovers, which they defined as spending more than one day in the same location. Researchers then used mathematical modelling to predict how reducing the amount of time resting while flying home could help birds to speed up.

Their modelling considered the average flying speed, the total migration distance and how birds can vary their speed in response to changing environmental conditions. In the future, birds may actually be forced to take longer breaks as their stopover grounds will likely be affected by climate change, says Dr Schmaljohann:

“When birds experience unfavourable conditions, such as drought, heavy rain and cold temperatures, the feeding conditions deteriorate. The feeding conditions directly affect total speed of migration via stopover duration.”

Adapting on the fly

This new research may help to explain why birds appear increasingly unable to keep pace with climate change, says Dr Stephen Mayor, an ecologist from the University of Florida, who wasn’t involved in the study:

“You would think that birds which migrate thousands of kilometres with the changing seasons would be experts at adapting to climate change, but this evidence suggests birds are much less adaptable than we might hope – probably because the climatic changes are so rapid and variable.”

The full paper The limits of modifying migration speed to adjust to climate change, Nature Climate Change can be seen here

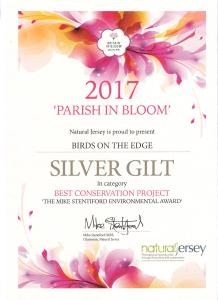

In what has become a tradition, each year at around this time Birds On The Edge can unveil the updated list of Channel Islands birds. With kind support from our friends in the very active birding communities in Guernsey, Alderney, Sark and Jersey the list, updated to the end of 2016, can be downloaded

In what has become a tradition, each year at around this time Birds On The Edge can unveil the updated list of Channel Islands birds. With kind support from our friends in the very active birding communities in Guernsey, Alderney, Sark and Jersey the list, updated to the end of 2016, can be downloaded  What has changed since the last list (to the end of 2015)? Well, that is very obvious to anyone looking closely at the species records and stems from the launch last year of the

What has changed since the last list (to the end of 2015)? Well, that is very obvious to anyone looking closely at the species records and stems from the launch last year of the

From

From

From the

From the