One of this year’s wild-hatched chicks arriving at the aviary. Photo by Liz Corry.

By Liz Corry

Fledging news!

Previously on Choughs…cue theme music…On 27th June Beanie baby was the first of four wild chicks to appear at the aviary with parents, Kevin and Bean, by its side.

Six days later another chick arrived. Unringed, but accompanied by Green and Black, and sneezing and wheezing, so it wasn’t hard to determine which nest it came from. It wasn’t hard to find a name for the new chick either. Lil’ Wheezy, who clearly wasn’t well, but it had made it to the aviary, so it’s odds were looking up.

A wild-hatched chick arrives for the first time at the aviary with parents begging for food. Photo by Tanith Hackney-Huck.

The third chick made an appearance on 5th July. We knew which nest it came from because of we could see pink and black leg rings. We didn’t know who it’s parents were. Well, not until it started guzzling food down its throat provided by Lee and Caûvette. This meant that our Les Landes pair had been travelling 9km away from their nest and the group finding food for their chick.

The news of this chick also means that another of our four hand-reared choughs has successfully bred in the wild; Dingle (fathered two in 2016), Caûvette and Bean. Poor Chick-Ay has yet to find a dedicated partner.

The fourth and final chick was spotted flying around the quarry on 6th July. Again, we knew which nest it was from, but did not know the parents. Two days later we were in for a pleasant surprise. Q and Flieur, a new pairing, led their chick over Sorel Point to join the flock feeding at the aviary.

This now brings the total number of free-flying choughs in Jersey to 38. Almost a quarter of which were wild born in Jersey. There is a video of the group in flight on Jersey Zoo’s Instagram page or just click here if you don’t have an account.

Lil’ Wheezy gets wormed

We needed to worm the sick chick that was now visiting the aviary twice a day. It couldn’t be done straight away. We needed the chick to become accustomed to flying in and out of the aviary in order to trap it inside. It took a good week for Lil’ Wheezy to grow in confidence and fly all the way in at each feed.

A wild fledgling caught up under licence to treat for nematodes. Note the bill colouration due to its young age. Photo by John Harding.

Patience paid off on the 19th when the team were able to trap it inside and catch under licence. Dave Buxton fitted leg rings and the Vet gave it a wormer before being released back to it’s parents and the rest of the flock.

Classic reaction to a vet holding a needle. Photo by John Harding.

MSc project wraps up

Guille finished collecting data for his research at the end of this month. He now has the delight of returning to Nottingham Trent University to make sense of it all. I will let Guille explain in his own words…

“Birds, and other animals have personalities. Consistent behaviours that are different between individuals, maintained through time and favouring -or not!- the survival of the individuals and their successful breeding.

Studying the boldness-shyness continuum in choughs. Photo by Liz Corry.

With the choughs I am looking at a classical behavioural trait: the boldness-shyness continuum and how it might affect survival.

Basically, if you are a bold bird you may be good at defending your food patch from others, get stronger and healthier and be able to feed your nestlings properly. However, if you are a very bold bird that would not leave the food patch even when there is a falcon approaching, you are in serious trouble.

I want to see if we can predict how far the released choughs will go to find food everyday just by looking at their personalities. Some studies have already shown that boldness has an effect on habitat use and distance travelled, which may be useful in a project like this one, where every bird is highly valuable and the distance they will travel will increase the chances of finding more food, or getting lost! If a correlation is found, it would help the project team to select which birds should be released depending on what behaviour is best to assure survival in the area.

Does Lee’s personality type predispose him to travel several kilometres away from the release site to feed? Photo by Mick Dryden.

For assessing their boldness, I presented them a squirrel-proof bird feeder that they had not seen before, as they have their daily supplementary feeding in open trays. I recorded the latency of each bird to pick food from it for the first time, during 15 minutes. After that, they were given their daily meal and I would not repeat the test until approximately ten days later, so they would not get used to it. Finally I gave every bird an average boldness score based on how long they took to pick food for the first time.

This year’s wild chicks were clearly not shying away from the feeder. Photo Guillermo Mayor.

Assessing the distance travelled was the fun part, as they had lost their radio tags. I had to become another chough and follow the group during their morning stroll. They leave the roost by 5am, returning for the 11am feed. I learnt lots about chough behaviour in the field. I saw their games, love arguments, gang fights, first trips of their chicks, but still they are very complicated birds.

By the end of July, after having cycled every single track of the north coast, I had a bunch of observations, from which I would pick the furthest point from the roost I saw each bird. Some of them were a bit surprising, such as Trevor and Noirmont. I found them perching on a German WW2 cannon, south of Les Landes. They looked like nobody could mess with them. I would definitely keep an eye on those two.

The two and a half months passed too quickly and I wish I could have stayed longer. The support I received from the project staff was amazing, and I would definitely recommend anyone that has cool ideas that would help the project and the broad bird recovery knowledge to think about doing some research here.

I am currently in front of the computer, missing the field and the choughs, and for now it seems that the boldness was consistent, which is good news! I really hope I can come back soon and see the noisy choughs again soaring over the windy cliffs, and all the lovely people who were like a family for a summer.”

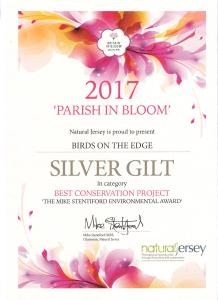

Birds On The Edge wins a RHS award

Birds On The Edge received a Silver award in the conservation section of the annual ‘Parish in Bloom’ event, a hugely popular and well supported national floral competition held under the professional auspices of the Royal Horticultural Society.

Glyn Young met the judges and Mike Stentiford on Sunday 23rd July to show them around Sorel to see the grazing flock of sheep, conservation crop fields, and the choughs. Although only two choughs showed up!

More information about the Parish in Bloom event run by Natural Jersey can be found at http://www.parish.gov.je/Documents/NatJerBrochureA4_ParishSites.pdf.

In what has become a tradition, each year at around this time Birds On The Edge can unveil the updated list of Channel Islands birds. With kind support from our friends in the very active birding communities in Guernsey, Alderney, Sark and Jersey the list, updated to the end of 2016, can be downloaded

In what has become a tradition, each year at around this time Birds On The Edge can unveil the updated list of Channel Islands birds. With kind support from our friends in the very active birding communities in Guernsey, Alderney, Sark and Jersey the list, updated to the end of 2016, can be downloaded  What has changed since the last list (to the end of 2015)? Well, that is very obvious to anyone looking closely at the species records and stems from the launch last year of the

What has changed since the last list (to the end of 2015)? Well, that is very obvious to anyone looking closely at the species records and stems from the launch last year of the

From

From

From the

From the

We worry about our puffins. We worry a lot and not without good cause. Our puffins have probably been in trouble since humans and their hangers on, the rats, dogs, cats and ferrets that follow them, first turned up in Jersey. Or walked along the peninsula presumably. And it’s not like the puffins could have been totally casual in their choices of nest sites before arrival of humans – wolves, foxes, stoats and weasels didn’t need us to show them where the seabirds were. Picking places to breed where wolves can’t get to is probably a lot easier than choosing rat-free ones. It’s a surprise that the burrow-nesting puffin even made it this far – nowhere else will they nest where rats are even vaguely close by.

We worry about our puffins. We worry a lot and not without good cause. Our puffins have probably been in trouble since humans and their hangers on, the rats, dogs, cats and ferrets that follow them, first turned up in Jersey. Or walked along the peninsula presumably. And it’s not like the puffins could have been totally casual in their choices of nest sites before arrival of humans – wolves, foxes, stoats and weasels didn’t need us to show them where the seabirds were. Picking places to breed where wolves can’t get to is probably a lot easier than choosing rat-free ones. It’s a surprise that the burrow-nesting puffin even made it this far – nowhere else will they nest where rats are even vaguely close by.

And what of the threats, do we know more about these? We know that our birds are unlikely to access somewhere to burrow thanks to the attentions of unwanted mammals. But how bad is this and how many of the pesky mammals are there on the cliff tops? Invasive mammals expert Kirsty Swinnerton is planning to find out and think up ways perhaps of getting rid of them. Or at least keeping them safely away from the birds. Local expert, and chough monitor, Keith Pyman has also wondered whether our fulmars, which colonised Jersey in the 1970s, might not be blame-free too. At least in not helping the precarious position of our puffins.

And what of the threats, do we know more about these? We know that our birds are unlikely to access somewhere to burrow thanks to the attentions of unwanted mammals. But how bad is this and how many of the pesky mammals are there on the cliff tops? Invasive mammals expert Kirsty Swinnerton is planning to find out and think up ways perhaps of getting rid of them. Or at least keeping them safely away from the birds. Local expert, and chough monitor, Keith Pyman has also wondered whether our fulmars, which colonised Jersey in the 1970s, might not be blame-free too. At least in not helping the precarious position of our puffins. Fulmars are never normally any threat to nesting puffins but these petrels, who can spit some pretty foul stomach contents at anyone annoying them, probably don’t normally get that close to burrowing puffins. However, here in Jersey, fulmars nest on the ledges and mouths of cracks and crevices – do they block the puffins’ nests? Puffins find it hard enough to approach their Jersey homes anyway (puffins in big grassy colonies simply throw themselves into the ground and run to the burrow) those using small rock crevices find the precision approach difficult without the threat of the spitting fulmar. Keith has noted fulmars in the places where in years past he saw puffins disappearing underground.

Fulmars are never normally any threat to nesting puffins but these petrels, who can spit some pretty foul stomach contents at anyone annoying them, probably don’t normally get that close to burrowing puffins. However, here in Jersey, fulmars nest on the ledges and mouths of cracks and crevices – do they block the puffins’ nests? Puffins find it hard enough to approach their Jersey homes anyway (puffins in big grassy colonies simply throw themselves into the ground and run to the burrow) those using small rock crevices find the precision approach difficult without the threat of the spitting fulmar. Keith has noted fulmars in the places where in years past he saw puffins disappearing underground.

The UK Government has released a

The UK Government has released a